Ahren Warner is 26, his first book-length collection is Confer

, published by Bloodaxe, but several of its poems are also contained in his earlier Donut Press book, Re:. I bought this on a whim when I bought Apocryphya, as I thought I recognised the name. This was because Confer was a PBS recommendation in Autumn 2011. I remember deciding not to buy it because of this: “About suffering they were never wrong, The Old Masters… // Though, when it comes to breasts, it’s a different story.” and a very weird and uncomfortable feeling I got reading the poem ‘Métro’, about how a woman in a crowd reminded him of a type of face that is “just asking to be cut down.”.

I may have been unfair.

He does seem to have high hopes for his poems, quoting Lucian Freud’s desire for “paint to work as flesh… to be of the people, not like them. Not having a look of the sitter, being them.” to illustrate the sense by which many of his poems “attempt embodiments of place that are best understood against the inevitable flux of the places themselves; a kind of parallax, for example, between Paris as one might actually experience it and Paris as it is (not as it has been experienced) in the poem.”

There’s a lot of influence evident in Warner’s work – inevitably vastly more than I’m privy to myself. He namechecks Nietzsche, Eliot, Cranach and Derrida amongst many others, and dips into several European languages – of which Greek is clearly the hardest to take in your stride, with poems titled Έρινύες (Furies), αί μοΰσαι (no idea but the poem is about London Bridge) and Διόνυσος (Dionysus).

I have a soft spot for found poetry – a collage technique of sorts whereby words and phrases from other sources are chopped up or pinned together to show something new and interesting. There’s an example here – ‘Carolina’ which comprises lyrics from songs with the title in their name. You wouldn’t know though, it somehow speaks with one cohesive voice (or at least a well practiced chorus of voices) despite the various sources.

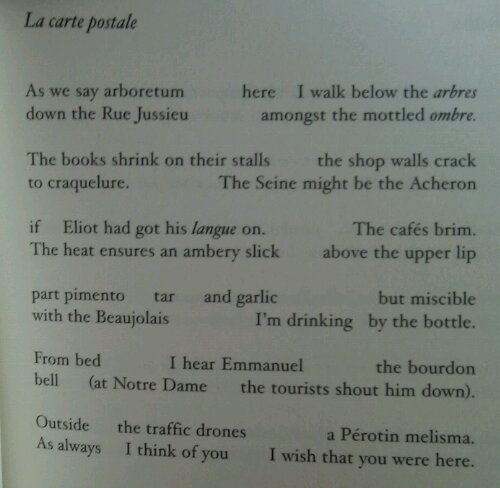

I was mystified when I read the piece in the PBS Bulletin about one of the forms he favours – he said that these poems “shun normal punctuation and find their grammar in a kind of spacing dependent on uniform line lengths to bestow a common musical measure […] which attempts to offer a greater range of intonational and affective pauses in order to perform a forceful but complex music: the ideal of a fugue con fuoco, perhaps.” – which at the time I dismissed as pretentious bollocks. The selector said that these “are tabulations, and provide a subtly different music with their delicately poised net of words, their subtle contemporary music.”. This didn’t really instil any more optimism for them to be honest, though I remained intrigued as to what on earth exactly they meant.

These uniform line lengths are basically both right and left aligned – justififed through use of variably large spaces between phrases (rather than in, what, kerning?), creating a block of text with irregular gaps in it. On reading one, I was, in all honesty, struck by the way that it does, in fact, create a kind of music. Scepticism rebuked! It just stirred in me a desire to see if it was the shape of the poem or the lack of punctuation that created this effect. So, here is one – an image of the poem as it was intended to be read, followed by the words without the required spacing. Read the image first, and see what you think.

La carte postale

As we say arboretum here I walk below the arbres

down the Rue Jussieu amongst the mottled ombre.

The books shrink on their stalls the shop walls crack

to craquelure. The seine might be the Acheron

if Eliot had got his langue on. The cafés brim.

The heat ensures an ambery slick above the upper lip

part pimento tar and garlic but miscible

with the Beaujolais I’m drinking by the bottle.

From bed I hear Emmanuel the bourdon

bell (at Notre Dame the tourists shout him down).

Outside the traffic drones a Pérotin melisma.

As always I think of you I wish that you were here.